ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — While lumbered with economic crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic and tensions between its major political parties, the Kurdistan Region was the primary target of two Turkish operations against alleged Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) bases.

Turkey, too, is suffering from the economic and social fallout of the pandemic, as well as domestic political tension – so what exactly does it hope to gain from its cross-border operations?

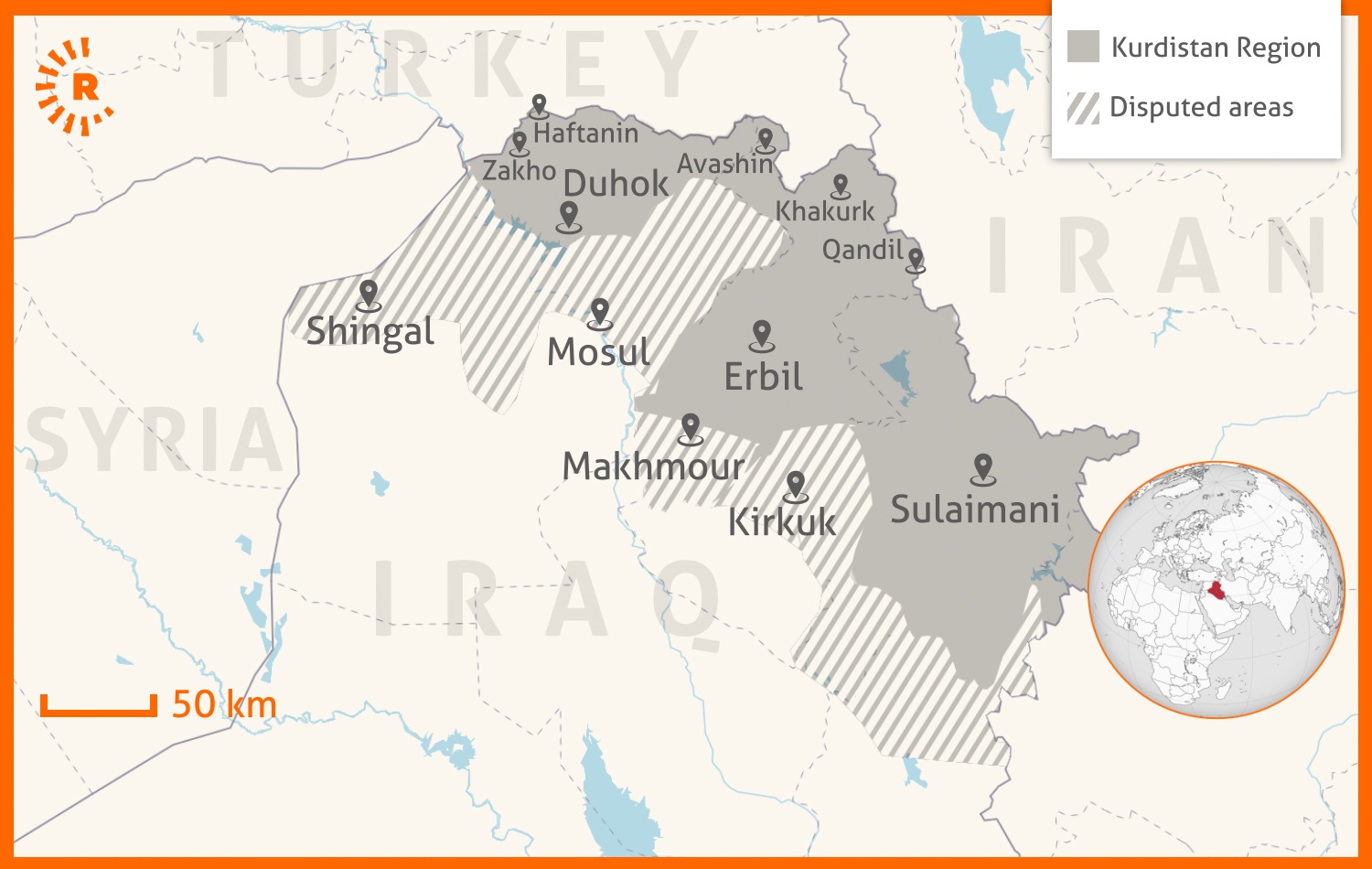

Ankara launched air campaign Operation Claw-Eagle against suspected PKK positions in the Kurdistan Region and the disputed territories on June 15. Its air forces have hit scores of targets in the Kurdistan Region’s Haftanin, Zap, Gara , Avasin-Basyan, Qandil and Khakurk areas, as well as the disputed towns of Shingal and Makhmour, both home to significant populations of refugees and the internally displaced.

Two days later, Turkey launched the ground-based Operation Claw-Tiger in Haftanin, involving the airdrop of commando force members into the Haftanin area of Duhok province. A further dispatch of Turkish commandos into the Kurdistan Region was made on June 21.

Turkish airstrikes killed at least five civilians in Duhok and Erbil provinces in two days beginning June 18. Ankara has announced the deaths of several PKK fighters, as well as two of its own soldiers. The PKK has not acknowledged Ankara-announced casualties to its own fighters, but claims to have killed several Turkish soldiers and downed at least two helicopters.

Turkey’s defense ministry claimed in its first statement after Claw-Eagle’s launch that the offensive came after PKK “attacks on our military bases and regions increased day after day.” It also more broadly claimed that the PKK has “threatened the security of our people and borders.”

Pointing to more long-term aims from Ankara, the PKK claimed in a June 17 statement that the aim of the Turkish offensive is to invade its headquarters in a region on the Iraq-Iran-Turkey border known as the Medya Defense Areas, “following the occupation concept it is developing.”

Over a week since Claw-Eagle began, neither Turkey nor the PKK look ready to relent. Turkey conducted airstrikes on Zakho, Duhok province for the eight day in a row on Wednesday, while Murat Karayilan, the PKK’s second most senior leader, vowed to continue countering Ankara’s campaigns.

“We will show resistance in any place they go to… We will show them a historical resistance and our comrades have vowed for that end,” Karayilan told the PKK-affiliated Sterk TV on Monday. Graphic: Maps4news, Sarkawt Mohammed / Rudaw

Graphic: Maps4news, Sarkawt Mohammed / Rudaw

Rehabilitating a strongman image

Amid blows dealt by economic crisis and coronavirus, and international scrutiny of its involvement in the Libyan and Syrian conflicts, military operations against a PKK vilified in the national conscience for decades serve as an opportunity to reinforce a strongman image for an increasingly worn out Turkish public.

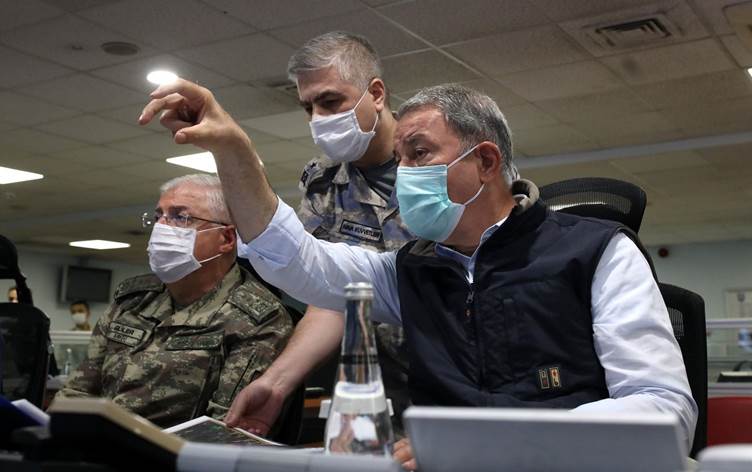

For Aykan Erdemir, Senior Director at of the Turkey Program at the Washington-based, nonpartisan Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) research institute, Ankara’s manicured presentation of the operation’s launch is to serve as a boost to a dented domestic image.

“Ankara’s publicity campaign featuring well-curated photos of the Turkish defense minister and the military’s top brass was a sign that there was also a significant domestic motivation for the operation,” Erdemir told Rudaw English.

The timing of the operation strikes Erdemir as significant, with the anniversary of a July 15, 2016 failed coup attempt blamed on former Erdogan ally Fethullah Gulen looming.

“In the run up to the fourth anniversary of Turkey’s failed coup attempt and right before the restart of the highest-profile coup trial following a COVID-19 hiatus, Operation Claw-Eagle has also served to bolster the defense bureaucracy’s tarnished image,” added Erdemir.

Among those targeted in Erdogan’s extensive post-coup crackdown on political opposition is the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), a pro-Kurdish, left-leaning party that the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has accused of ties to the PKK since the party’s inception.

The HDP vehemently denied any links to the coup, but four years on, the party is subject to waves of crackdown that include its democratically-obtained gains.

Ankara has removed most of the HDP’s 59 mayors elected in 2019 local elections, with over 20 detained for their alleged links to the PKK. The party held a five-day, cross-country march in protest of the crackdown earlier this month.

Anti-PKK operations alongside the target of the HDP for alleged terror links serves to homogenize Turkey’s Kurdish issue, Erdemir said.

“When coupled with the Turkish government’s ongoing attempts to criminalize the pro-Kurdish HDP and remove its elected members from office, Operation Claw-Eagle is yet another sign that Ankara has re-embraced its failed strategy from the 1990s of reducing the Kurdish question solely to a counter-terrorism matter and ignoring the complex political, economic, social, and cultural, and dimensions.”

However, Oytun Orhan from the Ankara-based Center for Middle Eastern Studies (ORSAM), believes that Ankara’s operations are detached from domestic political developments.

“Fight against terrorism is not directly related with internal politics. It is about security issues … PKK is Turkey’s main security problem and will fight against it regardless of the governments and domestic political issues,” he said.

Timing of the operations is not necessarily tied to events in Turkish politics, but to the PKK’s annual propulsion of its military activities in spring and summer, Orhan suggested.

Rattled by Rojava

Two long at odds Kurdish political groups appear to inching closer to political agreement in northeast Syria, an area known to Kurds as Rojava.

In a milestone development, the ruling Democratic Union Party (PYD) and opposition Kurdish National Council (ENKS/KNC) reached an initial political agreement last week – much to Turkey’s chagrin.

Ankara has branded the PYD as the Syrian extension of the PKK, and claims that unity talks involving the former are “legitimizing” the latter.

Turkish foreign minister Mevlut Cavusoglu has twice expressed his country’s opposition to the talks, warning it will treat the ENKS with the same animosity it doles out to the PYD if the two Rojava parties reach a final deal.

Turkey has felt compelled to act on its disapproval of developments on the other side of its southern border, according to Erdemir.

“The timing of the Turkish military operation, which coincided with the initial agreement between the KNC and the PYD in northeast Syria, shows that it is as much a political message to various Kurdish political actors in the region as it is an assault against the militants of the outlawed PKK,” he said.

Orhan agrees that the PYD-ENKS talks are a motivating factor in its air and ground operations in the Kurdistan Region.

“Turkey is disturbed by these negotiations. So with this operation, Turkey also gives a message to actors who are in contact with the PKK,” Orhan said.

How long, what scope?

Turkey appears not to be budging from its operational stance. Iraq’s foreign ministry has twice summoned Turkish Ambassador Fatih Yildiz to protest the operations, but Yildiz told Turkish state-owned Anadolu Agency (AA) on June 16 that his country is “concerned that Iraq has not taken any concrete steps to remove the PKK from its land.” He claimed that their operations are in the framework of “the right to self-defense.”

Orhan situates Turkey’s current operation within years of military operations in the Kurdistan Region, and believes Ankara’s cross-border campaigns will continue for as long as the PKK remains in the Kurdistan Region and the rest of Iraq.

“This operation is the continuation of previous cross border attacks between 2015-2019. And probably, will continue until PKK continues to exist in Iraq,” he said.

Turkish presence and operations in the Kurdistan Region seem as though they won’t just be continuing at current levels, but expanding. An unnamed senior Turkish official told Reuters on June 18 that Ankara plans to establish new temporary military bases to “prevent the cleared regions from being used for the same purpose again. There are already more than 10 temporary bases there. New ones will be established.”

The current operation will continue “for as long as necessary, until it reaches its objective,” the official added.

A push of the core of the PKK-Turkey conflict beyond its borders comes first for Ankara, before any elimination of the PKK from the Kurdistan Region, US-based analyst Ceng Sagnic told Rudaw English – making it likely Turkey will be conducting operations in the Kurdistan Region for the long haul.

“Turkish strategy has the export of the conflict with PKK to beyond its borders, namely the Kurdistan Region, as a priority; and that success in the effective elimination of the PKK presence in the Kurdistan Region comes second. These operations are designed to transfer the epicenter of the conflict to Iraqi Kurdistan,” Sagnic said.