WASHINGTON – Long hailed as a haven for minority groups, Iraq’s northern autonomous Kurdistan region has turned into treacherous territory for many Iranian dissidents and refugees escaping persecution from Iranian authorities, rights activists say.

The most recent victim was Mostafa Salimi, who escaped prison along with dozens of other inmates after rioting in the Iranian city of Saqqez to avoid contracting the coronavirus.

Once outside the prison, Salimi knew where to seek refuge. The 53-year-old Iranian Kurdish activist immediately crossed the border into the neighboring Kurdistan region of Iraq, where he thought he would be protected from Iran’s notorious judicial system.

His short stay in Iraq was disrupted when local Kurdish security forces arrested him and deported him to Iran, where he was swiftly executed last month.

In prison for 17 years, Salimi had been charged with “waging war against God” for being a member of an Iranian Kurdish militant group.

Unsafe haven

Since 2016, more than a dozen Iranian asylees and refugees have faced death threats, physical assaults, kidnapping and assassination attempts, according to rights groups, lawmakers and government officials.

Iran has frequently waged missile attacks against Iranian Kurdish militants based in Iraqi Kurdistan.

“Iran can get away with a lot [in Iraqi Kurdistan], whether it’s assassination, kidnapping or detaining somebody who crosses [over] the border,” said David Pollock, a Kurdish affairs expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Acting with impunity

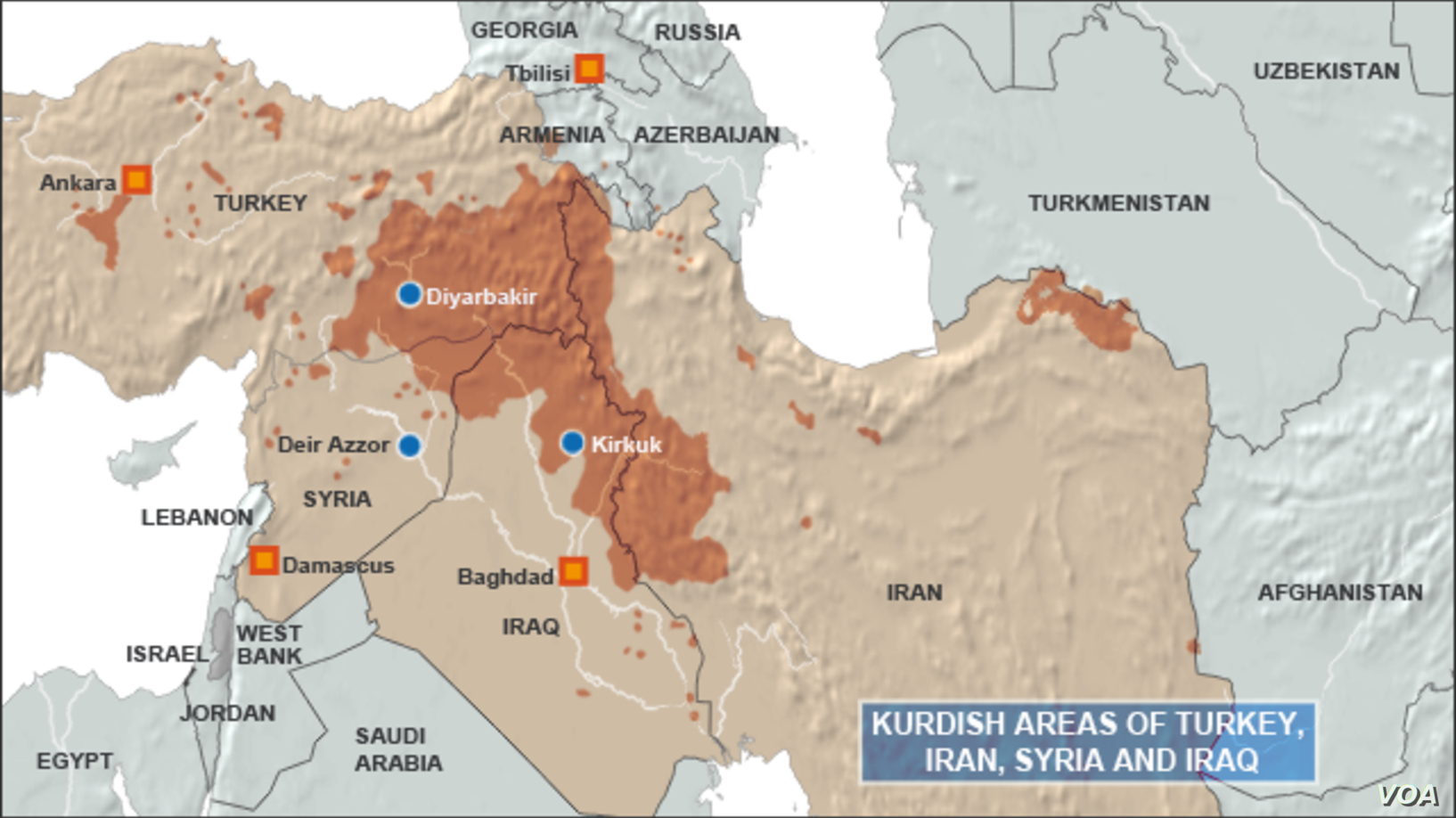

An exact number of Iranians living in Iraqi Kurdistan remains unknown, but the figure is believed to be in the thousands, populating nearly a dozen camps in Irbil and Sulaymaniyah provinces. Most are ethnic Kurds or family members of officials for two secular Iranian Kurdish opposition groups — the Kurdistan Democratic Party-Iran and Komala.

Both groups, which have armed military wings, maintain bases in northern Iraq and seek autonomy for Iran’s 5 million Kurds.

On March 11, Adnan Rashidi, editor of the Kurdistan Human Rights Association, was physically assaulted by several masked men who had come for his hard drives containing the names of activists working secretly inside Iran. The attack left Rashidi with a broken arm and bruises on his head.

Rashidi said he had no choice but to comply, as they allegedly started filming his wife naked and threatened to sexually assault her.

Two arrests have reportedly been made in connection with the attack, but many doubt that justice will ever be delivered in such sensitive cases.

“In no way do the courts get to the bottom of these issues,” Gulistan Mohammed, deputy chairwoman of the Human Rights Committee at the Kurdistan Parliament, told VOA.

“I really have no hope that the courts would ever do their job and that the law would be above us all. In reality, neither the courts nor the judges are independent here,” she added.

There is precedent for Mohammed’s pessimism. No arrests have yet been announced for the 2018 bombing that targeted the car of a senior KDP-I official, Salah Rahmani, in Irbil. The attack killed his 33-year-old son.

Iranian influence

Some experts view the growing violence against Iranian dissidents in Iraqi Kurdistan as a sign of Iran’s increasing sway in a region long seen as a pro-U.S. enclave.

“All in all, looking at this picture, one concludes largely due to Iran’s long arms in the region and its pressures on local authorities, serious threats still face the dissidents who have sought refuge in Kurdistan,” said Mohammed A. Salih, a doctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, who closely follows Iran’s activities in the region.

The continued pressure on Iranian dissidents in Iraq highlights Iran’s activities after the death of powerful Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani during a U.S. airstrike in January. Soleimani was a frequent visitor to the Iraqi Kurdish region.

Most Iranian immigrants in northern Iraq have no proper documentation or a clear pathway to citizenship. With their Iranian passports revoked or expired, they are effectively rendered stateless, noted Arsalan Yarahmadi, director of Hengaw, an Irbil-based group that documents violations against Iranian Kurds.

Partisan tensions

The Kurdistan region is ruled by two major parties that share political and military powers.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) is largely in control of cities such as Irbil and Duhok, while the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) considers the Sulaymaniyah province as a stronghold, which borders Iran. The two political powerhouses have long-standing tensions over influence and revenue.

When Salimi arrived in Sulaymaniyah province, he sought refuge in a mosque. Three days later, local security forces arrested him.

Salimi was initially told he would be taken for mandatory coronavirus quarantine because he was a visitor. But in a matter of hours, he was extradited to Iran, where close family members visited him in prison to learn the details of his escape.

A PUK official denied that Salimi had ever crossed into Iraqi Kurdistan.

“He has not been in Iraqi Kurdistan at all,” Saadi Ahmed Pira, a senior PUK leader, told VOA.

But Pira’s denial contradicts what VOA learned from Salimi’s Iran-based relatives, who shared the story on the condition of anonymity for fear of retribution from the Iranian government.

“Please let me kill myself, but don’t hand me over to Iran,” Salimi reportedly pleaded to Kurdish security officers, according to a family member.

Iran Human Rights, a Norway-based organization, has also detailed the escape, arrest and ultimate execution of Salimi.

A letter sent from the Kurdish Parliament to the KRG prime minister’s office, a copy of which was obtained by VOA and verified with three lawmakers, concluded that a Kurdish security unit in Sulaymaniyah deported Salimi to Iran.

“Since this is a moral, political and national issue, we find it necessary to be taken seriously and that the final results of the investigation be explained to the public,” said the statement, which was signed by five lawmakers — all members of the co-ruling KDP.

The issue has deepened the partisan divide between the KDP and PUK, with officials accusing each other of being puppets of foreign countries.

“Kurdistan is nothing but three provinces,” said Daban Mohammed, a member of Gorran, the third-largest Iraqi Kurdish political party.

“Two [provinces] are politically close to Turkey, while Iran holds influence over the political party in control of the other province,” he told VOA, noting that “these are two different interests and agendas that often diverge and clash, preventing us from having a united government.”

The KRG, which says it has formed a committee to investigate Salimi’s case, denied allegations that the top leadership was involved in the extradition.