Steve Sweeney talks to Chair of the British Alevi Federation Israfil Erbil about a pogrom Turkey’s government would rather they forgot

Just one month separates the founding conference of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in November 1978 and the events known as the Maras Massacre, when Islamic fundamentalists and Turkish fascists (Grey Wolves) started a week-long killing spree which left more than 100 Alevis murdered and many more injured.

Forty years ago today saw the beginning of one of the most brutal and bloody stains on Turkey’s history. The atrocities that took place in the Turkish city of Maras between December 19 and 26 1978 have left deep scars for the Alevi community, and with nobody held accountable, the quest for justice continues today.

Many have claimed there is a link between the rise of Kurdish, Alevi and revolutionary movements and the state-planned massacre that took place in Maras. The targets of the killings were Alevis, Kurds and revolutionaries with official records showing 111 people killed, although others put the death toll closer to 500.

Hundreds of buildings were attacked and burned down during the massacre, including the offices of the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey (Disk), the teaching union building and the offices of the Republican People’s Party (CHP).

At the time around 80 per cent of the Maras population were Alevi – the second largest belief group in Turkey. Socially progressive and drawn to left-wing and revolutionary politics, they were seen as a threat to the unity of the Turkish republic and had defied attempts by the authorities to assimilate minority groups, seeking to maintain their culture, beliefs and way of life.

Discrimination against the Alevi was built into the Turkish constitution of 1925 which prevented them from building Cemevi – Alevi spiritual houses.

Maras province was once home to a large Armenian population who suffered during the genocide that took place at the hands of the Ottoman empire between 1915 and 1923. It was a state-orchestrated massacre that saw the systematic extermination of 1.5 million Armenians.

The town of Zeitoun – now known as Suleymanli – offered fierce resistance to the numerous attempts by the Ottomans to bring them under government control, which included the burning of villages and populating the surrounding area with Muslims. They were to be punished during the ethnic cleansing of Armenians, with many killed and deported.

Kurdish Alevis have a long history of persecution in Turkey. The backlash following the the Kocgiri uprising in 1919-21 saw hundreds of Alevi Kurds killed and many more forced into the mountains. The 1938 Dersim Massacre saw the bombing and attempted annihilation of the population and just months later, the killing of around 100 Alevis in the villages of Erzincan.

Eight Alevis were killed and at least 100 injured in the Malatya massacre in April 1978, during which time mosques were used by Turkish nationalists to encourage attacks on Alevis following the killing of the mayor.

They roused anti-Alevi sentiment by proclaiming: “We are losing our religion. They are putting bombs in mosques, too.” Around 20,000 people gathered in the city to attack Alevis.

In the September preceding the Maras Massacre, the city of Sivas saw Muslims and Turkish nationalists kill 12 Alevis and 200 injured with hundreds of houses and buildings attacked in the Alibaba neighbourhood.

Many witnesses and survivors of the Maras Masacre say that it was planned and then covered up by the state. Secret documents revealed the involvement of the Turkish security services (MIT) –including a relative of Grey Wolves leader Alparslan Turkes – and there are persistent allegations that the CIA helped plan the massacre, with Alexander Peck the operative named in government files.

Some 804 faced investigations for their role in the massacres receiving what have been described as largely symbolic sentences –although they were released in April 1991. The 68 people who played leading roles in the pogrom were never arrested or investigated.

Others that helped plan the massacre and have evaded justice include the former mayor of Maras Ahmet Uncu, who, while investigated by authorities, was later to become a far-right MP and has been treated as a witness to the events rather than a perpetrator.

On December 26 1978 martial law was announced in İstanbul, Ankara, Adana, Kahramanmaras, Gaziantep, Elazig, Bingol, Erzurum, Erzincan, Kars, Malatya, Sivas and Urfa. It was this series of events that opened the door for the military coup of 1980 during which thousands of leftists, revolutionaries and trade unionists were jailed, tortured and disappeared.

The Maras massacre started after a sound bomb was thrown into a cinema frequented by the right-wing on December 19. Blame was swiftly attributed to Alevis, “communists and leftists,” although it is believed that the device was planted by a police agent provocateur to spark the killing spree.

The violence worsened after left-wing teachers Haci Colak and Mustafa Yuzbasioglu were murdered on their way home from work on December 21. Their funeral was attended by more than 5,000 people, however Turkish nationalists and Muslim extremists continued to stir up tensions claiming “the communists are going to bomb the mosque, and will massacre our Muslim brothers.”

Chair of the British Alevi Federation (BAF) Israfil Erbil, who was just six years old at the time of the Maras massacre, explained that the mosques were used to whip up hatred of Alevis.

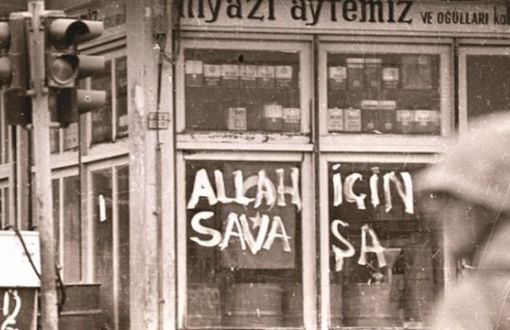

“Thousands of people came to Maras shouting Allahu Akbar. These people were from the same community, many knew their attackers.

“They grew up hearing that Alevis were sinners and that if you killed one you were guaranteed your place in paradise.”

He told me that the events in Maras were like a genocide, rarely seen in history. The attacks were notable for their brutality. Nobody was spared from the bloodbath with pregnant women, the elderly and children among those killed.

The iconic photograph of the Maras massacre showed surgeon Alaittin Gultekin Yazicioglu holding the dead baby of Esma Suna who was shot in her own home by Islamist fundamentalists.

He knew her family who were from an Alevi farming community and had settled in Maras from Elbistan. Her baby was killed as a bullet hit his spinal cord and the image of him holding its lifeless body became a symbol of the pogrom.

“When I took the baby out, with deep sadness in my heart, I showed it to the journalist in the operation room. I wanted to show this savagery to the entire world – to all human beings,” he explained.

It effectively ended his career in Maras. Most medical staff at the hospital were given letters of appreciation for their efforts, however because of the photograph Yazicioglu did not receive one. He was transferred to another region of Turkey shortly afterwards.

Erbil detailed the brutality of the atrocities, including a woman whose baby was cut out of her stomach and nailed against a wall – the message was that nobody was safe and they were prepared to kill future generations to wipe out the Alevis.

He accused the Maras authorities of hiding the graves of at least 40 people that were killed in the massacre. One of the central demands of the BAF is to find the bodies so they can be returned to their loved ones and given a proper burial.

“The authorities are refusing to tell us where the graves are because they are trying to cover the real numbers of those killed and also the way that they were killed.

“Many were beheaded. Women were raped and had wooden poles inserted into their vaginas, men were raped as well,” he tells me.

“A young boy was nailed to a tree by his forehead, like the crucifixion of Jesus. An 80-year old woman was raped and then buried upside down in a hole that had been used for baking bread.”

He said that when state officials came to the area following the massacre they found women who were naked and had been raped. Instead of helping them, the officers said: “They are not human, they have no shame.”

“It was beyond killing, it was beyond massacre, it was pure hatred,” he said.

The impact of the Maras massacre is still deeply felt by the Alevi community. Erbil described the massacre as a success for the state as thousands fled Maras, many to other parts of Turkey but also overseas.

Of the 300,000 that have arrived in Britain from Turkey, 80 per cent are Alevis, Erbil tells me. Many have connections to Maras, however Erbil fears that what he calls “the hidden history” of the massacre may be lost for future generations with many reluctant to tell their story.

He told me of a husband and wife who live in London who are unable to speak about what happened to them 40 years ago.

“She was pregnant and the baby was born at the minute they were being attacked. They had to escape so she wrapped the baby in a blanket and held him but he was crying.

“They needed to leave and in silence so the attackers didn’t hear. Because the baby was crying the man put the baby in a bin somewhere and started running. But his wife turned back and got the baby and then they ran.

“The boy is 40 and they live in the same house. It is difficult for him to face it.”

The Maras massacre is a dark stain on Turkey’s history which it would rather brush under the carpet.

“We are told ‘just forget it.’ Don’t come back to our city and scratch this ulcer and make it bleed again,” Erbil explains as he tells me he was branded a terrorist for coming to Maras in order to commemorate those killed and for continuing the fight for justice.

But he warns that authoritarian President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is using the same methods that led to the Maras massacre. Mosques are manipulating public opinion in his favour, particularly during elections.

And Erbil explains that a new generation are being brought up with the same hatred and distrust of Kurds and Alevis.

“I’ve seen it in my eyes from police officers who were not born at the time saying ‘we have done it and we will do it again,’ warning us to be careful.

“This danger has not passed. Hundreds of people were attacking us the first time we went in 2010. They were young, a new generation that has been raised with that ideology again.”

A ceremony due to be held in Maras on December 22 has been banned by the authorities, but Erbil insists it will go ahead and is planning to attend.

Meanwhile the struggle for justice continues. We owe it to the people of Maras and those struggling for peace and democracy in Turkey to ensure that the stories are heard and they are not forgotten.

The Erdogan regime continues its brutal attacks and oppression of all sectors of Turkish society, from journalists and academics to opposition MPs, activists and trade unionists.

It does so with the political and military support of the British government which does not wish to see the development of democratic forces in Turkey as it would threaten its imperialist interests in the region.

As we remember those who suffered and continue to suffer from the impact of the Maras massacre we must stand in solidarity with those fighting for peace and democracy today.