Ankara claims it’s helping displaced Syrians return home. Kurds and international observers accuse Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s government of demographic engineering.

NORTHEAST SYRIA—Just two months after the launch of Turkey’s most recent incursion into Syria, dubbed Operation Peace Spring, civilians’ return to areas now occupied by Turkish forces has already begun.

Turkey launched its long-anticipated operation in October in order to clear the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) from the border region of Syria and Turkey and create a so-called safe zone to settle millions of Syrian refugees who fled to Turkey over the course of the Syrian war. The Turkish government deems the YPG a terrorist organization and an extension of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has waged a decadeslong and deadly campaign for Kurdish autonomy inside Turkey.

According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), more than 75,000 people still remain displaced from areas in northeast Syria and are now sheltering in relatives’ homes and camps for internally displaced people after fleeing the Turkish operation. More than 17,000 people have crossed the border to Iraqi Kurdistan to seek safety, according to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees.

Considering the underpinnings of the operation, the return of Syrians to their homes in the northeast is highly politicized.

Various regional groups such as the Internationalist Commune of Rojava and the Rojava Information Center have long argued that Turkey is undertaking ethnic cleansing of Kurds and sees its most recent operation as part of this demographic change along Turkey’s borders.

Turkey, on the other hand, contends that it is paving the way for Syrians who have been sheltering in Turkey to return to their homeland, thereby restoring the population from before the Syrian war. Various media outlets have recently reported cases of Syrian Arabs returning to areas recently cleared of so-called terrorists, particularly the now Turkish-controlled areas of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain—towns that have always had a substantial Kurdish population.

For instance, Turkey’s state-run Anadolu Agency reported that about 70 Syrians, some of whom had lived in the border town of Sanliurfa for seven years, had crossed into Syria and returned to Ras al-Ain.

The Turkish Defense Ministry also stated that 295 people have recently moved from Jarabulus, a Syrian border town west of the Euphrates River, to Tal Abyad now that “peace and security” has been restored. These Syrians had allegedly fled the YPG an unspecified number of years ago and are returning to their homeland thanks to Turkey.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights has deemed this a form of engineered demographic change, noting that civilians only need to register their names with Turkish forces in order to be moved by a car escort that departs twice a day.

Mahmud Komiteya, a Kurdish community leader from Tal Abyad, fled the city after Turkey launched its operation and is now sheltering in Qamishli, in the far northeast of Syria. He recently spoke to Foreign Policy by phone, which regularly cut out due to poor service.

Komiteya said he was told by his Arab neighbor, who is currently looking after his home in Tal Abyad, that no one has returned to the city besides a few Arabs. “Some people are coming from outside the city … to delete the demographic, put other people there and remove our culture,” Komiteya told Foreign Policy.

U.N. data shows that approximately 123,000 people have returned to their place of origin since the start of the operation. Roughly half of these people have returned to places now controlled by Turkey. As of the start of December, Turkey had captured about 1,900 square miles, stretching from west of Tal Abyad to east of Ras al-Ain.

U.N. spokeswoman Danielle Moylan explained that of the number of people who have already returned—close to 102,000 went back in October—meaning approximately 83 per cent of the displaced who have returned did so in their first month of displacement. Given the deteriorating security situation, those who remain displaced are unlikely to return anytime soon.

Moylan also confirmed reports of approximately 300 families previously displaced from Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain who have recently returned to their areas of origin from Jarabulus, in addition to 200 Syrian families returning from Turkey.

But there is no evidence these Syrian families who were sheltering in Turkey once lived in Syria’s northeast. Furthermore, the return of families who were sheltering in Jarabulus for the last few years ignores the need for the most recent wave of internally displaced people to return, too.

The secretary-general of the Austrian Association for Kurdish Studies, Thomas Schmidinger, sees the transfer of people from other areas, including Jarabulus and Turkey, as a land grab.

“Nearly no one from Ras al-Ain fled to Jarabulus or Turkey [during the most recent operation], so the people going there now come from completely different regions of Syria,” Schmidinger told Foreign Policy. But they are taking over the homes most recently vacated by people who fled in October.

There has been a constant flux and various waves of internally displaced people and refugees in Syria’s northeast since the start of the Syrian war. In 2012, Ras al-Ain became a front line between the Kurdish administration and Turkish-backed opposition forces and militias.

“So the Kurds fled the region west of Ras al-Ain to the region under control by the Kurds in Jazeera,” Schmidinger said, referring to the eastern Syrian region that includes Qamishli.

The demographic makeup of Ras al-Ain has been fairly constant, though the most recent census—conducted in 2004—did not differentiate ethnicity. Schmidinger estimates Ras al-Ain was 70 percent Kurdish, up to 15 percent Arab, and 15 percent Christian Syriacs and other minority groups, such as Chechens and Turkmen. Tal Abyad had an Arab majority before the war. In 2011, 70 percent of the population was Arab and 25 percent Kurdish, according to the Washington Institute.

In 2015, when the Kurds captured the city from the Islamic State, thousands of Arabs fled the city, with many going to Turkey. Schmidinger contends that most of these people worked with or were affiliated with the Islamic State. Further, they may have feared retribution for having forced Kurds and other minorities to flee when the Islamic State took control in 2014.

“There was at least one village called al-Ballou where the Kurds kicked out the Arabs because the village was known for being very pro-ISIS,” Schmidinger said, using an acronym for the Islamic State. “The criteria for kicking people out was definitely not ethnicity, but political support for ISIS,” he added.

Amnesty International accused the Kurdish administration of forced displacement and home demolitions in 2015 and documented cases that had no justification on grounds of security or protection for residents.

According to Moylan at OCHA, at least 750,000 people were already displaced from the region before Oct. 9, when Turkey launched its operation. Now, it appears Turkey is bringing in Arabs who fled from Tal Abyad in 2015, as well as people from other parts of Syria and Arab refugees who had been living in Turkey for several years.

Komiteya, the Kurdish community leader from Tal Abyad, said the people being moved into the city now are originally from Ghouta, Idlib, and Aleppo and doesn’t believe they were once from Tal Abyad.

Indeed, it isn’t safe for anyone to return to areas now controlled by Turkish-backed forces. “The factions ruling over the area are heavily abusive, and in addition to this there are car bombs exploding also on a daily basis in the newly captured areas,” said Elizabeth Tsurkov of the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

She further argued that Kurds and Yazidis are particularly vulnerable to abuses by the Arab-led militias now controlling the area, and many of their houses have been seized by various factions of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA).

“We will [continue to] see the return of Arabs, the Chechens, but most Kurds will be forced not to return to their homes because of the violence and abuse they would suffer if they did,” Tsurkov said.

Komiteya, now sheltering in Qamishli, told Foreign Policy he would most likely move to Raqqa, the former Islamic State capital which is now under Kurdish control, rather than going back to his home in Tal Abyad. “I can’t go back because there are robbers and gangsters there,” Komiteya said.

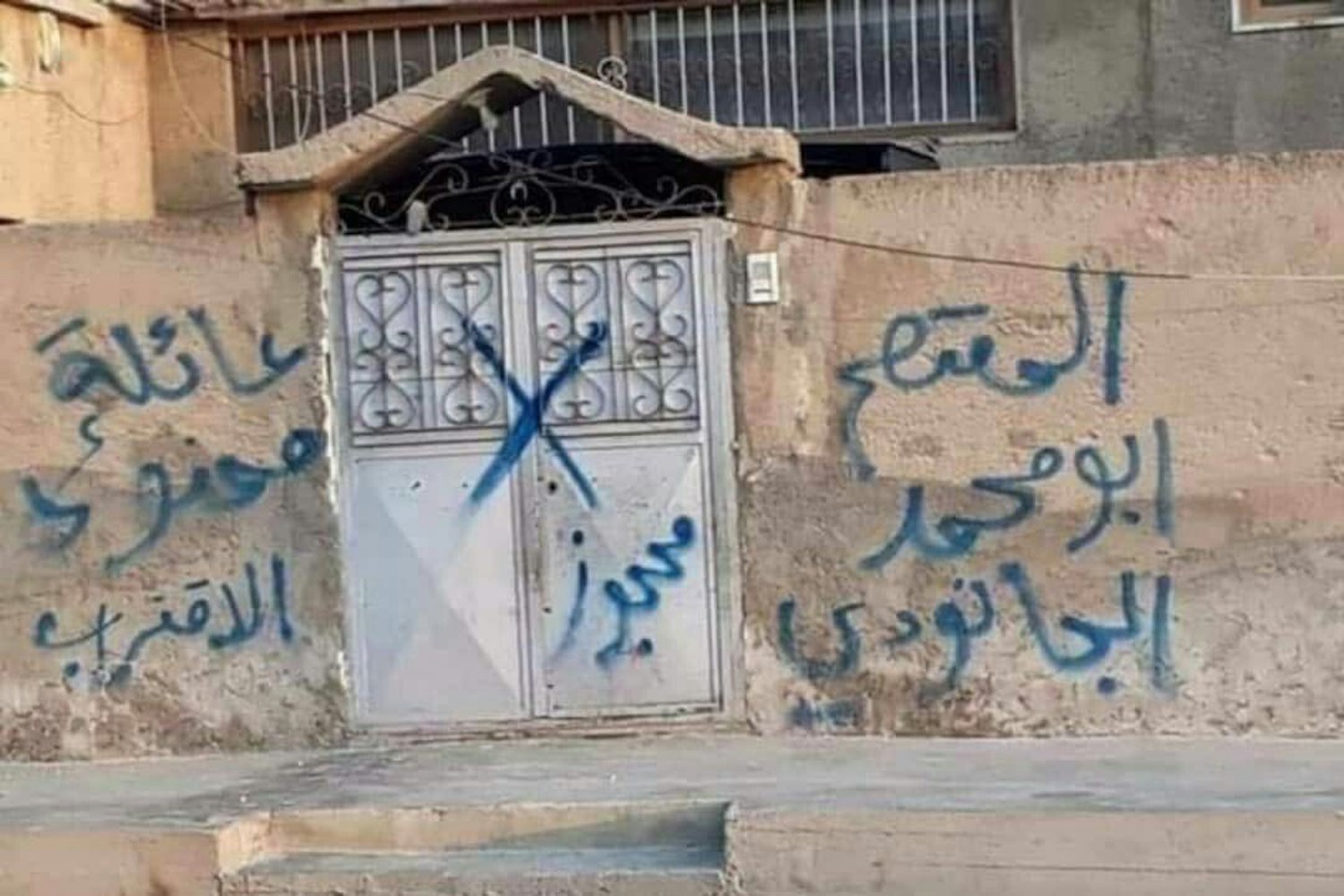

The marking of property available to loot and confiscate can be seen in video footage and photos taken in places such as Ras al-Ain, where names are painted on house walls. The names further show where some of these people come from, such as “Abu-Waleed al-Homsi,” signaling this person is originally from Homs, Syria.

The relocation of people not originally from areas like Ras al-Ain and Tal Abyad is quite evident from an administrative form distributed by Turkish backed forces, which fighters from any region in Syria can fill out to apply for their families to be relocated to areas now controlled by Turkey.

Tsurkov said the houses appropriated by various factions in the Syrian National Army generally belong to individuals accused of having ties to the YPG.

“[But] often times these people have no ties—they’re impoverished Arabs,” she added. “This is something we’ve been able to verify, both with fighters in the Turkish-backed factions as well as residents of the area who have fled.”

Human Rights Watch released a statement at the end of November detailing abuses carried out by factions in the Syrian National Army, including looting, confiscation of property, as well as preventing the return of Kurdish civilians.

While the premise of Operation Peace Spring was to establish a safe area for refugees to return to, the level of safety enjoyed by those who return appears to be based on their ethnicity—and comes at the discretion of the various factions in control on the ground.