MOSUL, Iraq – For centuries, it was a magnet for artists across the region and churned out Iraq’s best musicians – but recent years saw Mosul suffer a devastating musical purge.

For three years until last summer, the sprawling northern city was under the brutal rule of the Islamic State group.

In imposing a city-wide ban on playing or even listening to music, the jihadists smashed and torched instruments.

“It was impossible to bring my instrument with me whenever I left the house,” said city resident Fadel al-Badri, who hid his precious violin from the rampaging fighters.

Foreshadowing IS’ repression, the 2000s saw Al-Qaeda and other groups impose an ultra-conservative interpretation of Islam in several districts of the city.

But with Mosul freed from the grip of IS in July 2017, Iraq’s second city is embarking on a musical comeback.

“After the liberation, songs are back where they truly belong in Mosul,” said Badri, welcoming the return of evening celebrations and festivals.

The 45-year old violinist now has the pleasure of playing in public once more to an audience that claps hands and sings along to traditional local tunes.

After IS, ‘we sing’

Mosul has a rich musical history.

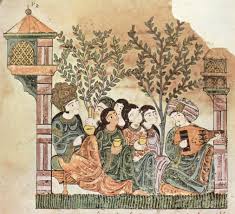

It is the home city of Ziryab, a musician who introduced the oud – the oriental lute popular across the Arab world – to Europe in the 9th century.

One of its more recent musical prodigies is Kazem al-Saher, the Iraqi crooner-turned-talent judge known around the region.

The city even has its own special genre of Arabic ballads, recognised across Iraq and beyond.

From folkloric shows and philharmonic concerts to weddings and other national holidays, song and dance have traditionally filled the streets and surrounding air.

But that meant nothing to IS, which ravaged Mosul’s heritage – musical and otherwise – when it took the city as part of a lightning offensive across Iraq in 2014.

The jihadists began by destroying the statue of celebrated ballad virtuoso Mulla Uthman al-Mosuli, and then turned their attention to destroying instruments across the city.

IS also forced musicians in Mosul to sign a pledge that they would never play or sing again, which was then posted in public places like mosques.

Singer Ahmed al-Saher, 33, said it was humiliating.

“I couldn’t leave Mosul after they made me sign because of my sick mother. I had to stay here under all that pressure and fear of the unknown,” he recalled.

Ordinary residents, as well as musicians, are keen to celebrate the return of artistic freedom.

“Terrorism failed in killing Mosulites’ love for art in all forms. It’s been born again, despite the destruction,” said Amneh al-Hayyali.

The 38-year-old brought her husband, son, and daughter to watch a late-night concert in a cultural centre in east Mosul.

“Today, after the dark era of beheadings, lashings, beards and veils being imposed on us… we sing,” she said.

Global artists welcome

But bringing Mosul’s artistic scene back to its former heyday will not be easy.

Tahsin Haddad, who heads the local artists’ syndicate, said he is keen to support public arts across the province.

“But we are in huge need of support from the central government in Baghdad, especially because Mosul currently has no stages, movie theatres, or art spaces,” he told AFP.

Without these venues, artists play in local cafes and public squares.

Celebrated Iraqi musician Karim Wasfi recently performed in a Mosul park where IS once infamously trained its child soldiers.

Earlier this month, Iraqi artists from around the country swarmed to the city for a cultural festival at Mosul University.

Performers stomped the dabkeh – a traditional Arabic line dance – and painters brought their works to display on the campus.

Glamorous Iraqi artist Adiba travelled from Baghdad with an entourage of peers.

“I am so happy to be in Mosul, singing here after it was freed from the grip” of IS, she said, moments before stepping on stage.

“Artists – Iraqi, Arab, foreign – should all come play festivals here.”